THE BENDS

•

THE BENDS •

The Question of Human Authorship and Gen AI

By: Annie Hanlon, Alex Porter, Tim Porter, Christina Lee Storm, and Rachel Jobin

The future of creative production depends on one question: who is the author?

In an era where AI can generate lifelike images, scripts, music, and animations, the entertainment industry faces a fundamental challenge - proving human authorship.

To understand the challenge, we can look back to a peculiar incident in 2011. A curious macaque monkey named Naruto, in Indonesia, grabbed a professional wildlife photographer’s camera and snapped a now-famous selfie. When the photograph was published, an animal rights group sued on Naruto’s behalf, claiming the monkey should hold the copyright.

The court ultimately ruled that only "persons or corporations" can legally claim copyright, not animals. The language of the U.S. Copyright Act simply doesn't grant animals the right to sue.

This ruling is the key to understanding the Gen AI problem. The U.S. Copyright Office agrees: If an AI model produces an image, video, or text without enough "sufficient human input," it simply can't meet the legal threshold for copyright protection. They've explicitly stated that just typing a few descriptive words (a "prompt") into an AI system is usually not enough to qualify the user as the human author.

Why is this a crisis for Hollywood? The entire financial structure of the M&E industry is built on clear ownership. Studios, creators, and investors rely on Intellectual Property (IP), the content's legally recognized ownership, to determine a project's value, finance its production, and monetize its distribution globally. Without clear authorship, there is no IP. Without IP, the economic model of film and television collapses. The industry urgently needs a way to prove a human artist, not the machine, remains the master of the final creative work.

Exploring the Copyright Problem in The Bends

To solve this IP crisis, innovators turned to R&D The Entertainment Technology Center at the University of Southern California (ETC) set out to understand how to demonstrate human authorship in generative AI workflows and thus apply for copyright protection for the R&D short film The Bends.

The Bends Producer, Christina Lee Storm, alongside Annie Hanlon, co-founded a startup launching Playbook AIR, a platform to tackle the trust layer. Together with Mod Tech Labs, led by Alex and Tim Porter, they are building a framework for documenting and verifying human authorship in generative production workflows.

Playbook AIR, is a security, provenance, and compliance platform that automatically tracks the human touchpoints within an AI-driven creative process. Enabled by the MOD automation architecture, it runs quietly in the background of a production pipeline, capturing metadata and authorship data without disrupting the artist’s creative flow.

For The Bends, the system tracked key elements of human creation, from director Tiffany Lin’s original character design to the iterative development of visual assets, ensuring that each step could be verified as the work of a human artist and ultimately provide the necessary evidence to successfully apply for copyright protection for the final film, securing its valuable Intellectual Property (IP).

The key is to capture enough data to ensure that all assets within a copyright submission can demonstrate human authorship. One of the technologies that facilitates the tracking of assets through the production pipeline is Wacom Yuify which adds a hidden Micromark to the artwork, proving it’s an artist's creation. It doesn’t change the quality of the art or how the image looks, it keeps authorship safe.

Copyrighting Generative AI Content is not Simple

The Playbook AIR enabled by Mod Tech Labs partnership was built around a simple goal: make provenance and authorship tracking invisible to the artist. Manual “prompt logs” and other workarounds are slow and incomplete. Artists cannot be expected to record every micro-decision they make while working. Automation allows these records to be collected passively, reducing friction while preserving essential proof of authorship.

Still, major challenges remain. Each studio and production pipeline operates differently, which means any provenance and authorship tracking system must be modular and adaptable. The architecture behind Playbook AIR must accommodate a variety of data sources and workflows without requiring additional effort from artists or engineers.

The broader legal landscape is equally uncertain. Recent court cases and Copyright Office guidance continue to redefine the boundary between “transformative” and “derivative” works, two distinctions that determine whether an AI-assisted output can be protected. With leadership changes and evolving standards at the U.S. Copyright Office, the industry remains in a precarious state of flux.

Within that uncertainty, The Bends serves as an R&D test case, a live experiment in how automation, documentation, and human-in-the-loop design can coexist within a generative production environment.

Copyright Enables Responsible AI

At a time when AI tools are becoming a routine part of filmmaking, design, and animation, the need for transparent provenance systems is critical. Without them, artists risk losing recognition for their creative input, studios risk releasing works with unclear ownership, and the acceleration of generative AI workflows in the entertainment industry risks an insurmountable problem.

By embedding provenance tracking directly into the production pipeline, projects like The Bends demonstrate that protecting human authorship does not have to come at the cost of innovation. The work of ETC, Playbook AIR, and Mod Tech Labs contributes to a growing conversation about responsible AI in entertainment and how creative ownership is defined, protected, and valued in the years ahead. Playbook AIR integrates the rigorous frameworks set by technical standards bodies and security organizations, while ensuring compliance with IP regulators and aligning with creative standards by industry professional organizations like the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (TV Academy) and the Producers Guild of America (PGA) to validate the protection of human artistry.

As AI continues to evolve, the lessons from The Bends highlight a path forward: automation that safeguards creativity, compliance that supports artistry, and collaboration between legal, technical, and creative communities to ensure that innovation and authorship remain aligned.

How Generative AI is Rewriting Key Aspects of Production Workflows

By: Sahil Lulla and Rachel Jobin

As AI tools reshape every corner of the filmmaking process, the Entertainment Technology Center (ETC) with support from Topaz Labs has been investigating how these technologies are redefining critical aspects of preproduction, postproduction, and cross-departmental alignment throughout the production pipeline. Some of these key shifts are granular aspects of the production pipeline, like how generative AI VFX plates must be upscaled before being integrated into the the VFX pipeline, unlike traditional workflows, whereas others represent broader changes relating to the way in which stylistic consistency is defined and maintained throughout a production. This article explores some how the ETC implemented these key changes on The Bends.

Upscaling Isn’t a Button—It’s a Workflow

There is a pervasive misconception that AI can instantly and cleanly upscale any footage to cinematic quality. While many AI upscaling tools exist, a studio-grade AI upscaling workflow is far more complex than a simple push of a button.

Traditional visual effects pipelines begin with high-fidelity 16- or 32-bit EXR files captured in linear color. These files are downsampled as the project progresses through post-production, resulting in a 2K–4K DCP, 8-bit SDR, or 10/12-bit HDR, depending on delivery specifications.

AI production inverts this process. Most generative models start from fragile 8-bit SDR outputs with gamma already baked in. But these 8-bit SDR files cannot simply be upscaled into cinema-ready plates via upscaling software. Any noise or artifacts baked into the source would be amplified by upscaling the source file, and these artifacts would be carried through every downstream step in the VFX workflow.

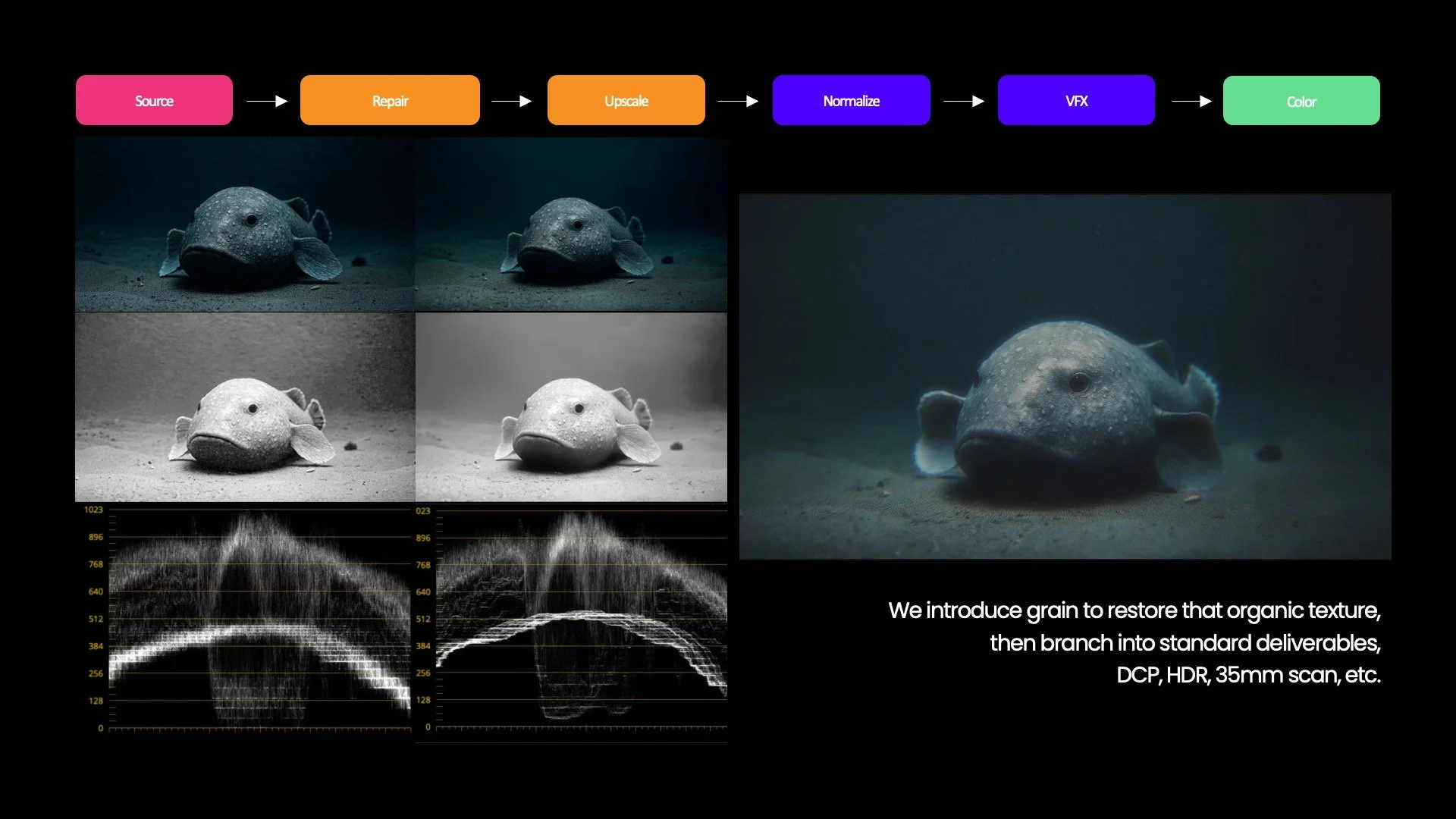

A traditional upscaling workflow compared to a gen AI workflow.

The ETC’s approach on The Bends combined traditional upscaling techniques with AI-assisted workflows in what the team called gen-AI–assisted plate restoration. The process began with Topaz Labs’ denoise model, Nyx, to remove compression artifacts from the 8-bit plates. These “restored” plates were then upscaled to 4K, 32-bit EXR using Topaz Labs’ Gaia High Quality (HQ) model and handed off to traditional VFX and DI. This hybrid plate recovery pipeline allows AI footage to behave like any other VFX plate.

Once the plate is upscaled, grain is reintroduced to restore organic texture, and additional methods are applied to mask any residual artifacts. Film emulation can assist in removing banding, but only after the AI output has been structurally cleaned. The result is then converted to standard delivery formats such as DCP or HDR.

A more conventional method employs inverse tone mapping, in which 8-bit plates are mapped up to HDR using data derived from deep learning and color science. This technique excels in plate matching between AI-generated and live-action photography, supporting a more classical grading workflow.

An AI-native approach would involve training a custom video model (or fine-tuning an existing one) to map SDR inputs to HDR outputs or even generate HDR natively. That kind of setup takes a lot of paired data, research, and compute to scale broadly, similar to what Luma Labs recently demonstrated. The ETC is currently exploring the feasibility of these two approaches.

Ultimately, upscaling AI footage is a pipeline design challenge, not a plug-in. Each step made when upscaling or otherwise preparing footage for postproduction has cascading effects on color, texture, and motion later in post. And while tools exist for individual tasks such as denoising, upscaling, and grading, the overall pipeline remains fragmented. The ongoing challenge is integrating these discrete tools into a cohesive, project-specific workflow.

Comparison of an 8-bit SDR plate before and after removal of compression artifacts. The final image has grain added back in.

Pre-Production in the Age of Generative AI

How does a generative AI production ensure that post-production and VFX remain aligned downstream? The answer lies in establishing stylistic consistency early in pre-production through the use of LoRAs (Low-Rank Adaptation).

In traditional pre-production, the creative DNA of a project begins with lookbooks, storyboards, and lens tests. These elements remain essential in AI-driven filmmaking, but their role has slightly shifted. The creative locus of AI pre-production is now LoRA creation, prompt engineering, and context engineering, each driven by the aesthetic framework established by elements such as lookbooks, storyboards, and lens tests.

LoRAs function as digital style libraries or lens kits, trained on curated imagery to reproduce specific aesthetics or lighting behaviors. Developing LoRAs is an iterative process: imperfect models are refined by combining their strongest versions or by stacking multiple LoRAs with varying weightings to achieve nuanced control.

This iterative process also helps develop a taxonomy of style tags, such as the lighting treatment or composition rules for a specific scene, allowing artists to recombine looks across shots. When paired with clip-based quality control and project-specific embedding libraries, this approach builds data consistency throughout the creative pipeline.

In effect, LoRAs and prompts replace lenses and LUTs as the new grammar of cinematic design. Learn more about how LoRAs were used to achieve stylistic consistency on The Bends [in this post].

AI as a Statistical Renderer—Not a Physics Engine

Once stylistic parameters are defined, understanding how AI interprets motion and realism becomes essential. Another key shift introduced by generative AI workflows lies in how filmmakers conceptualize simulation. AI video models often appear to mimic physical realism. Visual elements like a character’s hair blowing in the wind or of water splashing onto a beach would normally be generated using a physics engine like Houdini, but generative AI isn’t a physics engine.

Instead, generative AI systems perform probabilistic rendering, predicting pixels based on learned statistical patterns rather than simulating physical forces. Recognizing this distinction helps artists anticipate how AI models behave and determine where to apply traditional simulation tools for greater control. For as powerful as generative AI is, sometimes a physics engine is necessary to get certain movements to look realistic.

Understanding generative AI as a statistical renderer also points toward the next frontier: world models. Emerging systems such as Google’s Genie 3 promise to integrate tone, physics rules, and visual DNA into unified environments that maintain internal consistency across shots. Whereas today’s workflows resemble a patchwork of nodes, world models could consolidate these functions into a single coherent ecosystem, streamlining the entire AI pipeline.

A Collaborative Future for AI-Driven Filmmaking

Generative AI workflows blur traditional boundaries between departments. What begins in pre-production can directly influence upscaling, color, and compositing decisions downstream.

Success depends on early collaboration across technical and creative domains, and on understanding AI models not as “magic boxes,” but as probabilistic systems that expand creative potential through data-driven design.

AI isn’t replacing artists or engineers; it’s refactoring skill sets and breaking down silos. When creatives and technologists collaborate from the earliest stages, AI becomes not a shortcut, but a catalyst for new forms of artistic expression.

Consistency Is Key: Lessons on Generative AI The Bends

In less than three years, generative AI has evolved from an experimental toy to a regular presence in studio pitches, previs workflows, and even the festival circuit. Yet one challenge has stymied the full adoption of generative AI in long-form storytelling: establishing and maintaining control over outputs. This challenge also fuels many of the anxieties surrounding AI. How can artists maintain their creative voice when a machine is doing all the artistic work, and often doing so with inconsistent results?

Let’s say you’re making a short film about a recognizable animal whose physical form influences the character’s personality traits, like a blobfish, which was the protagonist for The Bends. How do you ensure that your protagonist not only resembles a blobfish but also retains their unique traits and quirks across successive shots? Furthermore, how do you maintain this same consistency in the environment from shot to shot, so it doesn’t look like your character is swimming in the depths of the Atlantic Ocean one moment but then suddenly finds themselves in someone’s swimming pool in the next?

Maintaining stylistic control requires more sophisticated tools and more complex data beyond simple prompt engineering and a few reference images of blobfish. There are a variety of tools that the ETC deployed on The Bends to ensure both stylistic consistency and creative control across the film.

ControlNet

ControlNet is a tool that helps condition[1] an output in a text-to-image diffusion model with greater precision than the text prompt itself. ControlNet extracts specific attributes from an input image and preserves them in subsequent generations. Various ControlNet models isolate different attributes. For example, Adapt ControlNet samples depth information from an image and, together with a text prompt, replicates that same depth information across all outputs.

ControlNets were essential in executing The Bends’ artist-driven workflow. The storyboard for The Bends was fed into ControlNet. The resulting output preserved the framing, character placement, setting, and shot length, and text prompts direct the model to fill in the remaining data to arrive at the final image.

A side by side of The Bends storyboard and final output.

LoRAs (Low-Rank Adaptation)

LoRAs (Low-Rank Adaptation) are another tool to establish control, but are fundamentally different from ControlNets. Diffusion models like Stable Diffusion are trained in massive datasets, but they are not trained on every possible datapoint. This is where LoRAs come in.

LoRAs are small, specialized models that can be trained on focused datasets, like a blobfish or a deep-sea environment, to generate results that more accurately reflect distinct characteristics of the input images. Otherwise, the outputs of a stable diffusion model alone can tend to look like a generic fish or seafloor that does not exhibit the same uniformity across the final film.

Both ControlNet and LoRAs extract and map certain characteristics of inputs consistently across outputs, but ControlNet extracts data from individual image inputs to guide certain elements in an output, whereas LoRAs are datasets that are used to establish the overall style of an image or character.

But where does the data for training a LORA come from?

Synthetic Data

For The Bends, the challenge was not only its unique characters and settings but also a required stylistic blend of realism and fantasy. No existing dataset captured that blend, so new data had to be created.

Creating synthetic data begins with a single image created under the direction of the creative team in a chosen style or setting. A diffusion model then generates matching images, iteratively expanding the set until an entire synthetic database exists in that same style and narrative world. This information can be used to train LORAs to generate outputs that both maintain creative fidelity from the original concept art and remain consistent across shots.

Synthetic data can encompass everything from general environments to subtle effects, such as recurring lens distortions that heighten realism. It was this approach that allowed the blobfish to remain grounded in its deep-sea habitat and for the visual language of the original concept art to carry through the finished film.

Merging 3D and AI

The final technique used on The Bends involved projecting AI outputs onto 3D elements. Scenes were broken down into simple 3D primitives such as cubes and spheres. Generative AI then acted like a render engine, retexturing these shapes to create the final elements of the scene. This is one of the more efficient ways in which to achieve world consistency, or consistency across background and foreground elements within a series of shots.

Maintaining uniformity across characters, environments, and scenes remains one of the greatest challenges in the adoption of generative AI for longform content. Yet tools and techniques like the ones employed on The Bends are steadily restoring authorship to the artist. Rather than dictating style, these tools safeguard intent, making the filmmaker’s vision the organizing principle of the work. For The Bends, the central aim was to discover how generative AI could serve as a partner in storytelling, efficient enough to streamline production, yet disciplined enough to preserve creative intent.

[1] Stable diffusion models work by adding noise to training data, then reversing that noise back into the original image. This process creates a “noise predictor,” which is used to generate images similar to the training data. The goal of conditioning is to guide this noise predictor so that the predicted noise results in specific outputs when the noise is subtracted from the image.